Language is one thing which unites the various forms, modes and practices of reading which we have been thinking about so far on this blog. On paper or screen, literary texts and the activities which readers engage in beyond the book are all made of and through language. As such, approaches in the field of applied linguistics can illuminate our understanding of reading: for instance by investigating how the language of literary texts works, and how we use language to talk about texts in social interaction. This post briefly discusses two quite different examples of the language of reading. First, I’ll look at a short extract from a reading group discussion about a novel and point out the way speakers use language to construct a collaborative reading of the text. Second, I’ll consider the language used in the pages of the same novel and the way the authors’ choices may influence readers’ experience of the text.

READING GROUP DISCUSSION

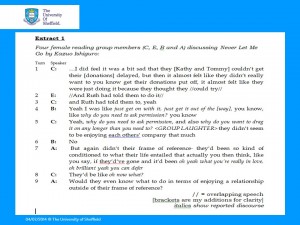

In the transcript ‘Extract 1’, four female speakers in a reading group in South Yorkshire are discussing the novel Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro, which was published in 2005 (you can read the first chapter here). The novel is told from the point of view of a human clone called Kathy who is destined to have her organs removed for medical science. She believes that she is in love with another clone called Tommy, and Kathy and Tommy hope that because they are in love the authorities will let them delay their organ donations for a while. In this extract, the reading group are discussing their reactions to the part of the novel when the clones find out that the authorities will not permit them to delay their operations. The group members are questioning the clone’s motivations for seeking the delay and expressing doubts about whether the clones really were in love in the ‘human’ sense of the word. (Click image to enlarge)

Talk as an act of reading

In their excellent article on reading group talk, Swann and Allington (2009) argue that reading group discussion is best seen as ‘one in a series of acts of reading’ for the group members taking part. Although the speakers start off by framing their utterances as a description of a past reading experience (C says ‘I did feel’ and B says ‘I was like’), they are not simply telling each other about their private experience of the text. This extract provides some good examples of the kind of collaborative reading, or ‘co-reading’ (Peplow et al, forthcoming) which often occurs in reading group talk.

‘Co-reading’ in the language of reading groups

Co-reading is evident in the way that speakers overlap and add information to each others’ utterances. For example in Turns 1-3, Participants C and E co-construct a representation of what happened in the novel. And in Turns 7-8 Participants A and C co-construct an imagined hypothetical scenario about what might have happened if events in the novel were different (‘if they’d’ve gone’). Here, participants use language to think together (a process Mercer (2000) calls ‘interthinking’) and develop a shared interpretation. The co-reading produced by the speakers here is also embedded in the social dynamics operating in the group. Notice how, for instance, speaker C introduces an idea about the characters in Turn 1 using the modalising expression: ‘it almost felt like’, and becomes more certain after receiving support rather than disagreement from other members of the group (‘they didn’t seem to be’, Turn 5). The group laughter that follows C’s contribution in Turn 5 is also evidence of the way the text being talked about is being ‘pressed into service’ as an interpersonal resource (Long 2003:147-8).

THE LANGUAGE OF NEVER LET ME GO

When I first heard this reading group talking about Never Let Me Go, I was quite surprised what they said about Kathy and Tommy. I had initially read the novel as a straightforward love story, but their discussion made me realise that there was something strange about the emotions and the relationship of these characters. An idea which is beginning to develop in ‘Extract 1’ and is returned to later in their discussion is the sense that the clones in Never Let Me Go are similar to humans in some ways, but also irrevocably different in others. This idea is also reflected in reviews about the novel, for instance Kerr (2005) writes:

“We root for Kathy – which is not quite the same thing as identifying with her. For, as authentic as her emotions may be, by definition she’s personality challenged” (Kerr 2005: page 2)

I’ve been interested ever since in how the way the novel is written may have influenced the kinds of claims which the reading group developed in their interaction and which are expressed in critical reviews.

Reading as an act of positioning

In the field of cognitive poetics, there has been a lot of work on the way that literary language encourages readers’ to respond emotionally to different characters: to identify with them or disapprove of them, for instance. I have argued elsewhere (Whiteley 2014) that the language of Never Let Me Go encourages readers to adopt quite a complex position in relation to Kathy – in which we both like and dislike her, and identify and disassociate with her. Close analysis of the language of the novel can illuminate some of the narrative strategies which may have influenced the reader responses described above.

For instance, aspects of the language which might work to encourage readers’ to experience a connection with Kathy (and see her as human) include:

- Moments where Kathy seems to address ‘you’ directly

- Detailed presentation of the characters’ gestures and dialogue, allowing readers to make ‘mind-reading’ inferences about their thoughts, feelings and goals

- The use of familiar metaphors to describe Kathy’s emotions in a way that we intuitively recognise

“Suddenly I felt a huge pleasure – and something else, something more complicated that threatened to make me burst into tears, But I got a hold of the emotion, and just gave Tommy’s arm a tug.”

Examples of emotion metaphors in Never Let Me Go (Ishiguro 2005: 170)

Aspects of the language of the novel which might work to problematise readers’ connection with Kathy (and emphasise the clone’s difference) include:

- The fluctuating second-person address. Although Kathy sometimes seems to address ‘you’ directly, at other times she seems to be addressing a fellow clone

- Moments when narrative perspective reveals the clones’ limited world knowledge and unfamiliar perception of the world. For instance, although the clones’ emotions seem familiar in some ways, their understanding of love is less familiar. Specifically, they view ‘love’ as something which has to be judged by the authorities who control them, rather than something they can judge and act upon themselves. This links in to readers’ comments about the clones’ capacity for love in ‘Extract 1’

“Madame’s got a gallery somewhere filled with stuff by students from when they were tiny. Suppose two people come up and say they’re in love. She can find the art they’ve done over years and years. She can see if they go. If they match. …what she’s got reveals our souls. She could decide for herself what’s a good match and what’s just a stupid crush.”

Example of the clones’ understanding of love (Ishiguro 2005: 173)

I think that linguistic analysis is a useful component in the wider, interdisciplinary investigation of reading practices represented in the Digital Reading Network. I’d be interested to hear others’ thoughts on the language of reading – and also what others who have read Never Let Me Go felt about the characters and the writing style!

See the forthcoming book The Discourse of Reading Groups by Peplow, Swann, Trimarco and Whiteley (Routledge) for more expansive discussion of these aspects of the language of reading.

References

Ishiguro, K. (2005) Never Let Me Go. London: Faber and Faber.

Long, E. (2003) Book Clubs: Women and the Uses of Reading in Everyday Life, Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Mercer, N. (2000) Words and Minds: How We Use Language to Think Together, London: Routledge.

Peplow, D., Swann, J., Trimarco, P. and Whiteley, S. (forthcoming) The Discourse of Reading Groups: Cognitive and Sociocultural Approaches, London: Routledge.

Swann, J. and Allington, D. (2009) ‘Reading groups and the language of literary texts: a case study in social reading’, Language and Literature 18 (3): 247-64.

Whiteley, S. (2011) ‘Text World Theory, Real Readers and Emotional Responses to The Remains of the Day’, Language and Literature 20(1): 23-41.

Whiteley, S. (2014) ‘Ethics’ in Stockwell, P. & Whiteley, S. (eds) The Cambridge Handbook of Stylistics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.