This is my second post as resident curator during February 2014 of the Digital Reading Network blog, covering the topic of “digital comics“.

“A book is a non-periodical printed publication of at least 49 pages, exclusive of the cover pages, published in the country and made available to the public.”

-UNESCO, 19 November 1964

“My work is dedicated to the proposition that the academic enterprise as a whole needs access to appropriate historical documents.”

-Randy Scott, 18 October 2001

For our third session of our Libraries and Publishing module at City University London, we will focus on comic books as an interesting case study whose analysis might help us understand some key issues around publishing and librarianship in the digital age.

“But comics?” You might ask.

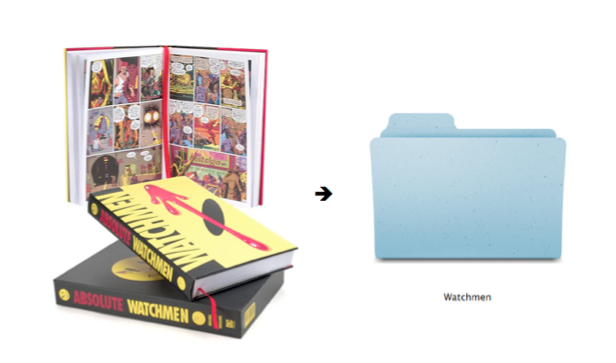

The history of comics has been defined to a large extent by comics’ stigmatised nature as subcultural material. In turn, this stigma has been incorporated in the ways in which the language itself is expressed in the form of different types of publications, such as hand-made mini- comics or luxurious slip-cased hardback limited, signed and numbered editions, a phenomenon which is related to the medium’s struggle for cultural recognition (Groensteen 2007; Lent 2001).

Moreover, self-imposed or external stigmatisation is expressed as formal and thematic constraints that have generated specific and complex cultural phenomena, including types of texts (newspaper strips, periodical comic books, graphic novels), genres (superheroes, political satire, humour, horror, romance, pornography, crime, biography, reportage, etc.) and dedicated ‘subcultures’ -there must be a better term – around them. Paradoxically, what arguably started at the dawn of the 20th century as an art form of and for the masses has been in danger of becoming a niche market only for the initiated. The artistic complexity of the texts has reached very high levels of sophistication, and so has the expense at which the books have to be produced, therefore increasing the cover prices substantially.

As the comic book market has become more specialised, its products have become more expensive, and its audience more elitist. As seen in the development of comics inthe last few years since the first publication of Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics (1993) onwards, digital technology would only further complicate things, sometimes in unprecedented ways.

The literature discussing the past, present, future and after-lives of books is considerable and increasing by the day, but comic books have been so far greatly excluded from the debate. With the notable exceptions of The Oxford Companion to the Book (2010) and Bettley’s The Art of the Book (2001), most literature in the fields of book history and topics concerning the history of writing and digital textuality, including studies of books as artistic objects and of the material page make no mention of comics at all, in spite of the fact they do refer to other forms of multimedia or text-and-image publications such as collage books and illustrated books.

The relationships between “content” and “document”, “text” and “publication”, “medium” and “message” are intricate, and today’s information professionals need to be aware of this. If, as Randy Scott puts it, comics “can help librarianship as a whole break some new ground in terms of proactive information handling”, it is because they are examples of multimedia that defy previous forms of categorization and description, both as messages (that which could also be described as “content”) and as publications (that which could also be described as “medium”, “form”, “material support”, etc.).

Randy Scott, the head librarian and founder of the Comic Art Collection, Special Collections Division of the Michigan State University Library, remains one of the best-known comics librarians in the comics scholarship field. In his pioneering Comics Librarianship. A Handbook, (1990) he writes:

A major reason that there are not enough histories, analyses and reference books about comics is that collecting comics is a very difficult job, and libraries have not been collecting well enough. Although there are some significant university collections of comics material, there are very few libraries that routinely acquire the best of what is newly published, even of political and non-fiction comics (1990:9).

The Library of Congress has never provided cataloguing for comic books as it does for almost every other category of published material. Until the late 1970s, no librarian anywhere on Earth would have been able to prove, using any standard library catalogues, whether such titles as Wonder Woman, Superman, or The Amazing Spider-Man even existed as bibliographic entities (1990: 14-15).

The need for specialized skills, the needs of a specialized readership, and a sense within libraries that the time is right to begin giving comics more serious attention, all these things make it seem possible that comics is a field that can help librarianship as a whole break some new ground in terms of proactive information handling (1990:23).

Scott’s remarks are relevant because they offer the context in which comics as publications were located in relation to academic information handling and humanities research at the time he was writing. During the same now-distant 1990s, George P. Landow, some seven years later, would argue that “any information medium that encourages rapid dissemination of texts and easy access to them will increasingly demystify individual texts” (1997: 84). If our understanding of “individual texts” has changed with the inception of the Internet (not to mention the Web), our understanding of comic books as “texts” (in this case as “publications”) should also change. How have things changed 24 years after Randy Scott’s Handbook was published?

The book Graphic Novels and Comics in Libraries and Archives: Essays on Readers, Research, History and Cataloging was released in April 2010. Edited by Robert G. Weiner, includes an article entitled “Webcomics and Libraries”, by Amy Thorne (pages 209-213) and includes an updated take by Scott on the Comic Art Collection at Michigan State University (pages 123-126). However, the volume seems to me very ill-equipped to deal with the transformations in comics publishing and libraries brought about the digital age.

During the first part of the lecture we will discuss the challenges that comics, as specific types of publications, pose to librarians, publishers, and booksellers of today.

Comics, in any form or format, are an international phenomenon. Casey Brienza (@CaseyBrienza) is a sociologist and Lecturer in Publishing and Digital Media at City University London’s Department of Culture and Creative Industries. I am incredibly pleased to say she will be our guest speaker for the second part of the lecture tomorrow. She has done extensive research on different aspects of Japanese comics (manga) publishing, focusing on, amongst other topics, the rise of manga in the United States and its implications for the globalisation of culture. Looking forward to tomorrow!

References

Bettley, J. (ed.) (2001) The Art of the Book. From Medieval Manuscript to Graphic Novel. London: Victoria and Albert Publications.

Groensteen, T. (2007) The System of Comics. Jackson: The University of Mississippi Press

Landow, G.P. (1997) Hypertext 2.0. The Convergence of Contemporary Critical Theory and Technology. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lent, J.A. (2001) “Comic Books”, entry for Censorship. A World Encyclopedia, A-D, Jones, D. ed. London: Fitzroy Daerborn

McCloud, S. (1993) Understanding Comics. The Invisible Art. Northampton, MA: Kitchen Sink Press

Priego, E. (2012). “Audio: Randy Scott on the Superpowers of Librarians (2001)”. The Comics Grid [blog post]. 29 June 2012. http://blog.comicsgrid.com/2012/06/audio-randy-scott-2001/ Accessed 13 February 2014. Web.

Scott, R. W. (1990) Comics Librarianship. A Handbook. Jefferson and London: MacFarland & Company

Suarez, M.F., Woudhuysen, S.J. & Woudhuysen, H.R. (2010). The Oxford companion to the book: Essays, A-C / Vol. 1, Oxford University Press

Weiner, S. (ed.) (2010). Graphic Novels and Comics in Libraries and Archives: Essays on Readers, Research, History and Cataloging. Jefferson, N.C. and London: MacFarland

—

This post appeared originally on my City University London blog, February 14 2014.