While I’m certainly no expert on digital comics (*bows to Ernesto*), I thought I’d use my first entry on the blog this month to share a few first impressions from a (previously sceptical) reader’s perspective. I’m sounding out a few digital creators I know for a follow-up blogpost and hope to use my next entry to put forward the opposite side and offer some perspectives and thoughts on writing for digital comics. But for now, here are some initial musings on my forays into reading comics digitally…

Firstly, and perhaps a bit obviously, having a tablet device makes all the difference. No longer am I tied to the desktop or my laptop, and it even feels a bit like a comic. Hold it portrait-fashion and you can see a whole page, if the designer of the digital content wants you to read it that way. Of course all these things hold true for the reader of books as well, but I think that comics readers in particular are a fetishistic lot. Many of us are collectors and thus archivists in our own right. Personally I blame my obsession with the object or artefact on the artistic narrative strand of comics – the artwork just makes me want to see it in hard copy! A screen seems like a very obvious barrier, removes the tactile appeal, and brings into play worrying questions of permanence.

Whether it’s on glossy paper in fabulous ink, or badly separated and printed on thin, low-grade paper, the object seems to be part of the whole experience of reading comics. I don’t feel this way about my books – although I love an old book, it’s less integral to the reading experience to me (and can even be an irritation with loose pages, fragile leaves and the like). Comics seems to conjure something different, perhaps due to that sense of disposability or the link with sensory memory from childhood. Ian Hague has written extensively on this in Comics and the Senses (Routledge, 2014), and the audience research of Mel Gibson also cites sensory data from her participants that stresses the importance of touch, smell and so on (see for example ‘British Girls’ Comics, Readers and Memories’ in Critical Approaches to Comics, ed. Duncan and Smith, Routledge 2012). The tablet is a step towards giving digital comics some type of aura (as I think many of us feel quite emotionally attached to our personal devices) but it’s got a way to go.

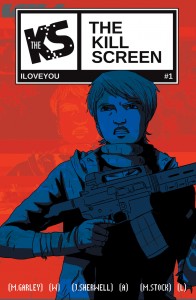

This isn’t the only issue to consider though, for the platforms are, of course, just as important and interesting as the device. I’ve got a few installed on my Ipad, the most-used of which is Comixology. It’s an app that allows you to read digital comics and lots of creators are now of course writing directly for it. For example I recently read The Kill Screen (written by Mike Garley, with artwork by Josh Sherwell and letters by Mike Stock), a comic written exclusively for digital publication by VS Comics. There’s something very nice about reading this particular title on a digital device since both the subject and appearance of the comic align with its medium. The Kill Screen is set in a world where humanity is nearly extinct as computer errors have travelled from the digital world into our own, destroying everything in their way. The artwork uses pixelation at various points, as characters literally disintegrate when infected with errors and viruses. In all honesty I can’t see this story working anywhere near as well on the printed page. It even made me want a little bit of animation, and I have always been dead against so-called ‘motion comics’ (because well, they’re not comics – but that’s a subject for a different blog). If you want to see what I mean you can find a free preview of #1 of The Kill Screen at http://mikegarley.com/the-kill-screen/ by the way – it’s great 🙂

However, reading this title using Comixology is quite different from reading a traditional comic, as each panel is zoomed in on individually. This definitely makes it easier to read, but for me seems quite counter-intuitive and disruptive (it’s too much like hard work to swipe or tap between every panel!). It also removes a lot of the narrative tradition of comics – for instance, there’s no page layout to situate the single panel within (the ‘spatio-topia’ (Groensteen, 2007) or ‘architecture of the page’), and there’s no natural page break to punctuate or create natural cliff-hangers by adding anticipation about what might be on the next page. It keeps the story moving quickly (and this is a fast-paced story) though, and arguably adds more suspense as each new panel is a complete surprise, but for me (as both a reader and a scholar) something is also lost.

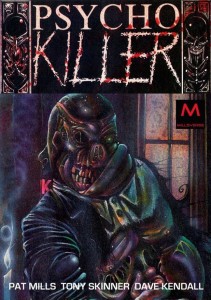

Recently I’ve also read Psychokiller (written by Pat Mills and Tony Skinner, art by Dave Kendall). This is a digitised version of a title first published by Toxic! in 1991. It’s a black comedy about a demonic doctor offering bizarre treatments to his patients, and is the first offering from the Millsverse, which is the new imprint from Pat Mills. Often named the ‘Godfather of British Comics’, Pat Mills (who is creator of 2000AD amongst many other things) is going to use this to publish out-of-print and new material. Interestingly, this title offers a bit more choice to the reader than The Kill Screen since you can choose whether to see the pages in their entirety, or double-tap the screen so it zooms into a single panel and then drag from panel to panel, or a combination of the two. This is more like the freedom traditionally accorded to comics readers – however the scanned pages of the comic itself detract somewhat from the original artwork (which is visceral and textured – almost painted in appearance) as the panel edges seem to vanish into blank white space. Contained within the screen of the tablet, this is a jarring juxtaposition.

I’ve also been using an app called Manga Storm. This gives me access to a variety of manga sites (mangafox, mangareader.net, MangaEden and so forth), which have free content (assuming I turn on my location settings so they can verify I am in an entitled area). As the content is free and comes from internet sites there’s less fancy options for reading – I can only zoom in and out – but handy arrows tell me which way to drag to access the next page (useful as I have a tendency to get lost in Manga sometimes) and again if I orient my Ipad to portrait then a single page will fit on nicely.

And this brings me to another advantage of digital reading within comics – it seems that if there isn’t a great demand for stuff or if you are in a particular location then you may well find it free. At the start of this year I discovered www.mangareader.net online which has free English versions of lots of very famous Japanese manga. I read loads of the horror classics for free (and if you’re interested I’d recommend Uzumaki and Tomie – both by Junto Ito, they are classics from the 1980s). Obviously I had no idea if this site was legal or not, but it seemed a little too overt to slip under the radar. As it doesn’t allow you to download titles, only to read them online, I decided it was probably legit, and went on to discuss this with a Japanese friend. She suggested it might also be because only the English translations are available, and a bit of follow-up research proved her right (as did the discovery and eventual downloading of the Manga Storm app mentioned above), since the kanji originals are nowhere to be found online.

Free stuff is great, and free books and comics are of course even better, but despite this it’s worth pointing out that both the titles I mention above are much cheaper than buying a single issue printed comic, let alone a graphic novel (a single issue of a monthly comic from Image may cost up to £3.95 GBP; but The Kill Screen was initially on sale for half that at £1.99 for # 1 and Mills released Psychokiller for £2.49). Brilliant though this is, there are issues of ownership to consider alongside this too – the Comixology titles will remain on my device or in the cloud as long as I leave them there, but are they truly mine to be free with as I wish? I can’t copy them, print them, hand them round in class, or lend them to a friend, for example. But in an age where the giants of publishing Marvel and DC seem to be losing popularity in favour of creator-owned imprints such as Image, digital publishing is also another great leveller of the playing field. It’s a great way to remove unwanted gatekeepers and censors, and to generate original work and allow new talent to surface.

Maybe these aren’t great insights, but I hope they are interesting starting points when considering the complexities of finding, buying and reading comics digitally. I look forward to hearing anyone’s thoughts – and will shortly attempt a follow up from the writer’s perspective…